-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

TOTW: Google's Project Ara Modular Phone May Be The Future Of SmartphonesOctober 30, 2014

TOTW: Google's Project Ara Modular Phone May Be The Future Of SmartphonesOctober 30, 2014 -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

TOTWs

Fighting A Robot In VR – Midas Touch Games’ BattleRig

08 years

It punched to the right. I blocked. Another punch, this time to the left. I blocked again. I quickly jabbed forward, knocking it back slightly. Regaining its balance, it took a step back, swinging its arms. I took the initiative, hitting it with a sharp uppercut to the jaw. Uppercuts seemed to have the best effect, I noticed. It went flying, landing head over heels. Relaxing, I took the HTC Vive virtual reality headset off. I had just demolished a large red battle robot in a one-v-one fight in virtual reality.

That was my experience with Midas Touch Games’ demo, BattleRig, at Augmented Reality World Expo in Silicon Valley. Midas Touch Games is a company that took on one of the largest challenges to VR yet: touchability, or the ability to manipulate and touch objects in virtual reality. It has taken long enough to make a VR headset capable of producing immersive games, videos, and experiences. But the whole idea of VR relies on immersiveness, and if you feel like you are in an unfamiliar physical world, it can make the experience lack credibility. If you touch an object, say, a book on a shelf, and it doesn’t react, that will temporarily take you out of the experience. In an ideal VR experience, everything you touch will react accordingly, therefore limiting the amount of times you actively think “Oh right, this isn’t real. I’m in virtual reality.”

While the ideal virtual reality experience is obviously still years away, Midas Touch Games and many other companies at AWE are helping to make that experience a reality. We have the headsets, we have the 3D models and 360-degree video, now we need to make that content interactive. And Midas Touch Games is doing just that. The one-on-one fight with a robot I was lucky enough to experience was just one example of their unique joint-based physics for VR. Joint-based physics have been in use in VR for inanimate objects for a while, but when it comes to more complex things like, say, robots, it just didn’t work. Midas Touch has created a joint-based system made especially for character-based simulations, what they call the Midas Physics Engine, a 3D engine for virtual reality characters.

While something called “Midas Physics Engine” may sound like PR jargon, it’s quite substantive. I’ve demoed a fair number of VR experiences, and while flying around a prehistoric landscape full of dinosaurs is stunning, the feeling that you are actually there goes away when you fly directly through a stegosaurus. But when you’re petting a dog, and it actually reacts to your touch, and you are even able to pick it up and push it around, as was the demo at the Midas Touch booth, the experience is much more immersive and memorable. And when you’re fighting a robot, when it’s reacting to your punches and vice versa, you really do feel like you’re there, and for me just simply interacting with the characters in your VR experience goes a long way for taking that next step towards the ideal, completely immersive VR experience.

Robin – Reddit’s Second Annual Large-Scale Social Experiment

09 years

Many early adopters of the Internet will remember the chat rooms of the ‘90s, small group messaging “rooms”, almost like group texts on modern smartphones. But these group messaging sites paired you with complete strangers, where people from across the world could discuss whatever they like. Chat rooms on websites like AOL rose to their peak prominence in the 1990s, but then gradually faded in popularity until their eventual demise a decade later.

Some have tried to resurrect the chat room on the modern Internet without much success; the Facebook-bought app Rooms attempted such a resurrection in 2014, but ended up being removed from the App Store a year later in October of 2015 due to a lack of popularity. Chat rooms seem to have fallen out of fashion, other platforms for Internet-wide communication rising to the top such as YouTube, Snapchat and Reddit. And yet, in an interesting moment of irony, Reddit, one of the websites that helped kill off chat rooms, brought them back for a short 8-day social experiment. Called Robin, as in round robin, the experiment was Reddit’s second attempt at leveraging their site’s large user base to learn more about people’s behavior on the Internet, the power of community, and simply how people would react to an interesting chat room mechanism.

For the uninitiated, Reddit can be fairly intimidating, a place where anyone with access to the Internet can interact and discuss any topic they please. While that may not sound all too enticing to you, the way Reddit is organized makes it much more palatable for the average person. Let’s say you’re interested in astronomy and would love to find a community of other astronomy enthusiasts. Just head over to /r/astronomy, the “subreddit” dedicated to everything to do with astronomy and astronomy news. On the astronomy subreddit, or a subreddit on any other topic, Reddit users can post links on that topic and hope they get upvoted to the front page. Every subreddit is a popular meritocracy, comprising primarily of a home page constantly updated with the newest, most popular links and/or discussions posted on that subreddit.

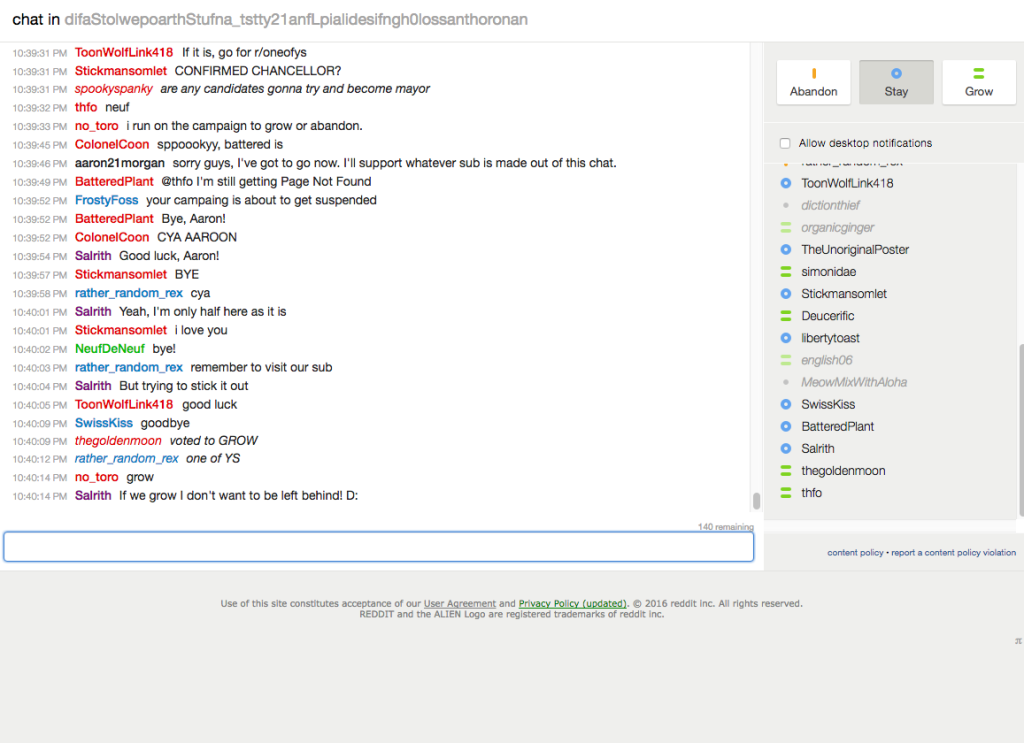

Robin isn’t a subreddit, or a feature on subreddits; actually, it started as just a button (not THE button, last year’s social experiment). When you clicked the button, depicting the outline of a Robin, you are brought to a page with one more button, this time saying “participate”. Upon clicking that button, you were brought into a chat room with you and one other random Reddit user. You and that Reddit user could chat for 1 minute about whatever you would like, and then you would have to vote on one of three options in the top right-hand corner of the page: stay, grow, or abandon.

Think of Robin as creating a village. If the majority of you and your randomly-assigned village-mates vote grow, then your “village” is merged with one of the same size. If the majority chooses stay, you build a wall around your village and plan to stay there for “life,” meaning you get a private subreddit made for that group that only the group members can join. And finally, if the majority votes abandon, the village is immediately closed and you can start again from the beginning, and if a couple of individuals vote to abandon then they alone are kicked out of the village. (in case you didn’t catch on, village means chat room in this analogy)

This would seem like a pointless voting mechanism if not for the fact that Robin in based on a chat room, a place where anyone can talk to anyone else in the world. Every time your group grows, the time you get to talk to your fellow “village-mates”, from 1 minute with 2 people, 3 with 4 people, 7 with 8 people, 15 with 16 people, and 30 with any higher number of participants. This means that, despite what you may think of people on the Internet, you can actually have interesting conversations. In my experience, as I spent a fair amount of time playing Robin when it was still running from April 1st to April 8th, the conversations you have change topic very fast and yet are still very entertaining and fun.

On top of that, the very mechanism of growing, staying, or abandoning sparks conversation, users campaigning for different votes. In one of my chats, I was part of an “ABANDON2016” campaign, as an overwhelming number of memes had flooded our chat. We were successful, to the dismay of the meme makers. In fact, for the people who vote stay, it’s not actually because they want a private subreddit with a bunch of random people who share most likely no interests; it gets boring after a day.

The conversations you have getting people to stay is the fun part, the part that makes it all worth it. The reason Robin was more than just a chat room was because it gave every single member of the chat a sense of attachment, to the people in the chat, and to the chat itself. Because it takes 30 minutes to get to the voting point of a 16 person chat, you have spent quite a while on any certain chat. Also, because of the way the chats merge, everyone feels like they had a part in starting what would later become a forum for global communication. In only a couple chats, I talked to people, usually men in their 20s, from places such as Turkey, the Netherlands, England, Israel, and more. This is the reception I got when I announced I had to leave a chat room, after participating in the election for 15-20 minutes prior:

(my username is aaron21morgan, and the bottom half of the running chat is mostly my fellow chat-mates’ response to my parting announcement)

In the end, after about a week up and running, Robin shut down just as The Button did a year ago. The largest chat ended up having 5,000+ people, and was apparently so big that the Reddit servers were having trouble just keeping it afloat. Now that the fun is over, we can look back on Robin as an interesting experiment and an entertaining game. We don’t often think about the fact that the Internet really does connect everyone in the world, and just the act of talking to a handful of them in a chat room can make that connection feel all the more real. Robin may have been a stupid Internet chat room to outsiders, but to those participated it helped humanize the average Internet commenter we encounter on an everyday basis. It may just be me, but having a simple conversation with someone thousands of miles away, even just for a couple of minutes, brings back the sense of wonder about the capabilities of the Information Age from back when the Internet was first being brought into mainstream culture.

The Monetization Conundrum Of Online Video

0With the possible exception of the Super Bowl, I’d bet it’s safe to say that nobody likes ads. Whether before a movie or video, in commercial breaks during television programs, or in the middle of your favorite podcast, nobody really enjoys being told to buy this product or use this service (often in a cringe-worth way) while they are enjoying their entertainment. Yet advertisements aren’t going away anytime soon; with the larger and larger audiences their ads are reaching, companies remain willing to allocate precious dollars to get their name out in every way they can. In the world of Internet publishing, ads have persisted as the staple of a creator’s income, despite significant shifts in the media landscape. But for online video, currently dominated by YouTube. advertisements have been a challenged revenue channel for creators hoping to earn a living.

I love YouTube and have a massive respect for the creators who have made it their full-time occupation to publish videos on the platform. These individuals spent an incredible amount of time and effort to become popular enough just to quit their day jobs and spend their time earning a living via YouTube. The sad part is that making a living on YouTube is harder than one might think. With popular YouTubers like PewDiePie making up to $7 million per year, it might be easy to regard YouTube as an easy path to fame and riches. But really, every YouTuber with even just 5,000 subscribers have put their heart and soul into their videos. As it is, money coming from ads just isn’t enough to allow YouTubers to start making videos full-time until they become very popular, a level which many never reach.

Let’s do the math. The average personal income in the United States is roughly $30,000. The current YouTube ad rate is a $2 CPM ($2 for every thousand views). To earn even the average U.S. income, a YouTuber creating weekly videos (a common schedule) would have to average nearly 300,000 viewers per video, an average usually only met by a YouTuber with around 2 million subscribers. (this varies from channel to channel) Of course, the rate at which you create videos is key in this calculation; if you make a video every day, the average view count drops to a more plausible 40,000. Compare that to the average CPM rate for TV, which is $19 (for an average 22-minute show). With that rate, you would only have to get 30,000 views per weekly video to reach the national average – much more sustainable.

Felix Kjellberg, aka PewDiePie, the most popular YouTuber on the platform. Last years, Felix sparked a small controversy when the public negatively reacted to his $7 million years income.

This isn’t just about YouTubers making more money because their media peers in television and film earn more. I’m not writing this out of pity for the struggling YouTubers who can’t earn a living wage yet are spending all their time trying to grow their audience. The reason the $2 CPM needs to be increased is because it simply isn’t enough to allow YouTubers to grow and make the great content we all want to watch. Take Olga Kay, a YouTuber with around 1 million subscribers across her five channels. In an article written in the New York Times, Olga talked about her hectic work schedule and about how “If we [her friends] were coming to YouTube today, it would be too hard. We couldn’t do it.”

Olga said in the article that she has made $100,000 to $130,000 every year for the last three years, which is a good income; yet she is still constantly stressed about finances, as much of that $100,000 goes straight back into her channels to pay for editors, equipment, etc. Let’s be honest: no one making twenty videos a week, almost three per day, especially with 1 million subscribers, should be that worried about finances.

This is the first part in Fast Forward’s two-part series on the YouTube’s advertisement and monetization conundrum. Stay tuned for the second article in the series over the next few days!

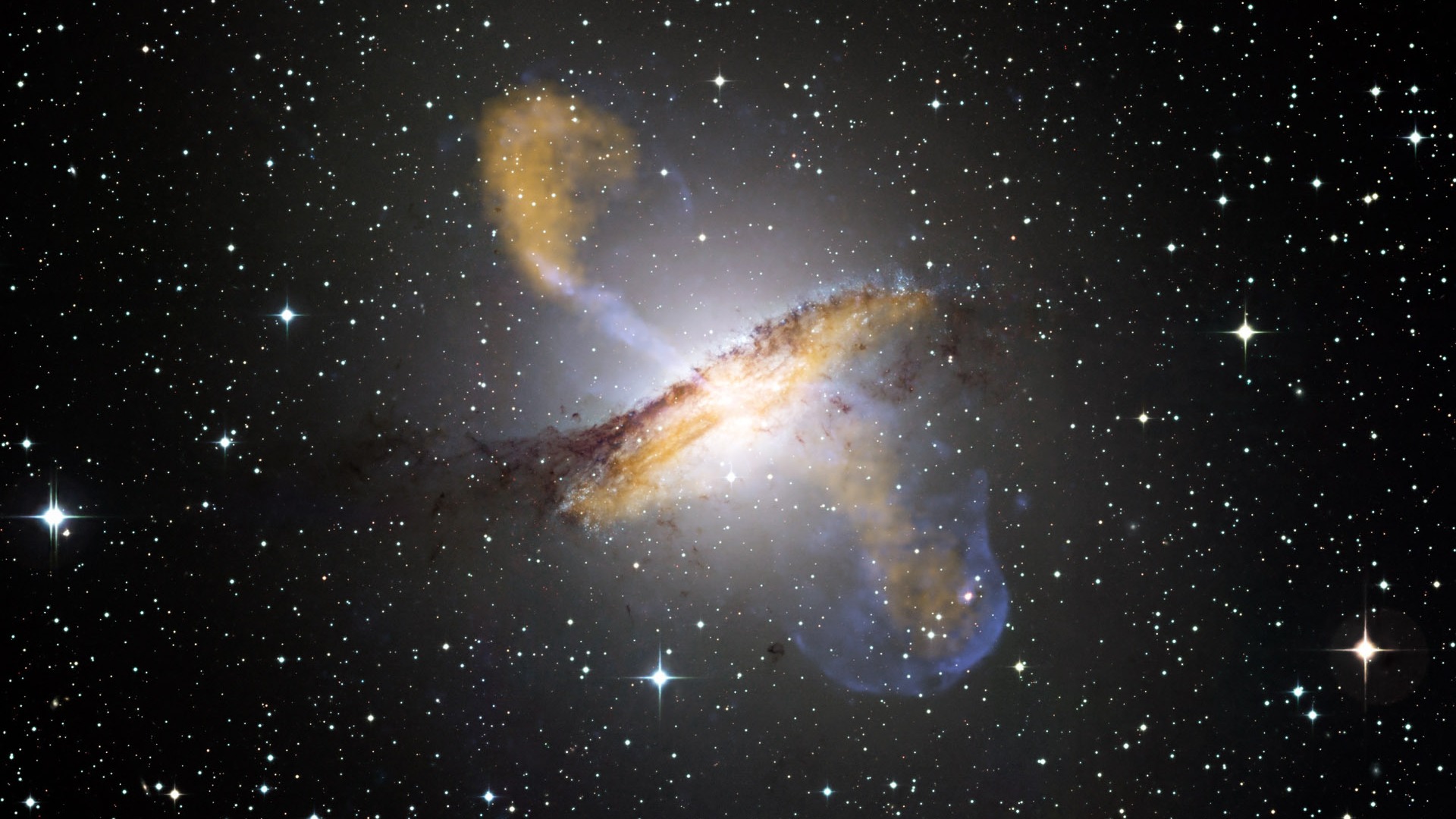

How Einstein Predicted The Future: A Story Of Gravitational Lensing

09 years

It’s 1916. A relatively unknown (see what I did there) physicist named Albert Einstein has just released a couple of papers about his very weird but interesting Theory of Relativity, and you can’t decide what you want to think about it. The papers have gained Einstein some popularity in the physics community, many agreeing with what he had to say, some disagreeing. Many years later, once the theory was proven through observations of Mercury’s orbit and other various tests throughout the years, Einstein became an internationally renowned, scientific rock star. Now it’s 2015, 100 years after Einstein introduced his ingenious theory. Einstein is still known as the epitome of human intelligence, and his fame and prestige is as widespread as ever, while the repercussions of his work still permeate the modern scientific landscape – so much so that it allows us to predict the future.

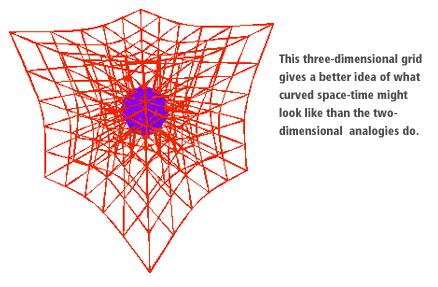

Before we get into the whole time travel stuff, it might help to understand more about what exactly General Relativity is. Despite the fact that Einstein is known as a genius worldwide, the specifics of what his theory actually means are lost on most people who haven’t extensively studied it. Whereas we see time and space as distinct, Einstein thought of them as one thing: “spacetime”. (Try not to think too hard about that merging space and time part.) Where Newton thought that there was this mysterious force called gravity that radiated from anything with mass, Einstein had his own theory, which assumed that, rather than using an enigmatic force to pull nearby things to it, objects with mass (especially large ones) curve spacetime. So, when following the easiest path through spacetime, which all objects naturally do, objects near another large object, say the Earth, naturally get pulled toward it. Now there’s a proposition for you: just by existing, you disrupt the fabric of the universe by curving it.

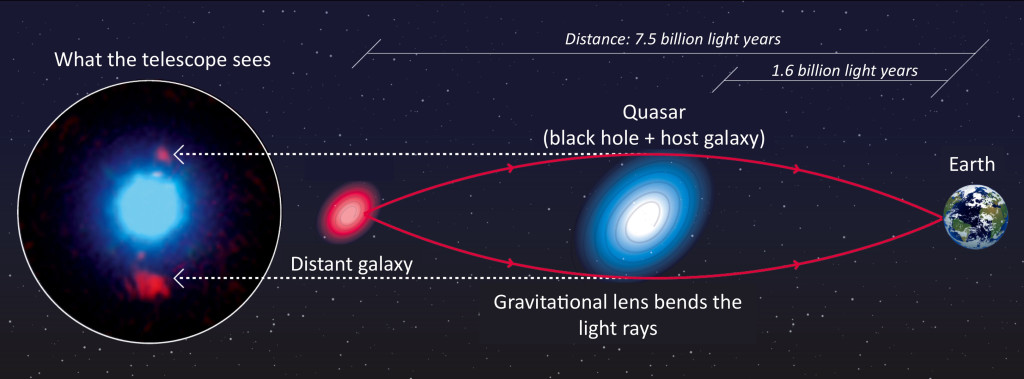

But it’s true, and as I wrote earlier, general relativity has been confirmed through many different experimental observations over the years. One such confirmation came through the discovery of a phenomenon that Einstein predicted in his papers, but never expected to be observed because of its rarity: gravitational lensing. Gravitational lensing occurs around large objects, though not just large as in the Earth or even the Sun, but large as in supermassive galaxy clusters. As it turns out, Einstein’s idea that things with mass curve spacetime not only explains gravity but also implies gravitational lensing. Because large objects curve spacetime, really large objects like galaxy clusters curve spacetime much more, enough so that light coming from behind the cluster becomes visibly curved.

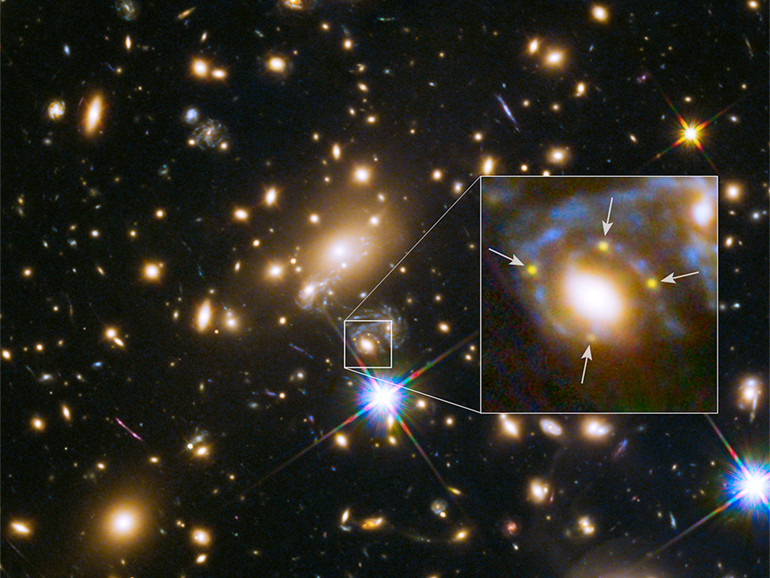

The light coming from an object directly behind the galaxy cluster, a smaller galaxy cluster for instance, will get curved around the cluster in the foreground and scattered away from its previous course, potentially toward the awaiting telescopes here on Earth. Einstein thought it would be unlikely that such a situation that we could observe on Earth would happen anytime soon; that a gravitationally lensed light source would happen in our direction, that the light would be lensed toward us, and that we’d be ready to receive it. He happened to be wrong on this one, as we have observed many instances of gravitational lensing in action over the years, the image below being one such example.

And one more thing: gravitational lensing essentially peers into the past. Because light takes time to travel to Earth, the farther away you look in a telescope, the further back in time you see. This doesn’t affect us in day to day life, but with large space telescopes like Hubble we can see billions of year into the past. Since gravitational lensing acts very similar to a telescope, taking light from far away and magnifying it, the foreground galaxy cluster acting as the lens, we can legitimately say that gravitational lensing peers into the past.

So, aside from being a fascinating phenomenon and an example of General Relativity in action, gravitational lensing has been used over the years be a tool to peer into the universe’s history, and recently, into the future as well. Researchers at the University of California, Berkley, published a paper in Science that detailed their observations and subsequent research on a supernova they named Refsdal after Norwegian astronomer Sjur Refsdal. Patrick Kelly, an astronomer at the university, noticed something odd while looking through photos taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. What Kelly noticed was what’s called an Einsteinian Cross, such as the one below:

An Einsteinian Cross occurs when gravitational lensing bends the light around a galaxy cluster and toward Earth in a way that projects 4 images of the same star around the forefront galaxy in the shape of a cross. In this case, the star was actually a supernova, when a star explodes in a fantastic burst of energy and light. Supernovae are one of the biggest and brightest events in the universe, releasing up to around 1044 joules, or the total energy released by an average star in it’s 10 billion year long lifetime. But supernovae are fairly rare, so you can imagine how lucky it was to observe a gravitationally lensed one.

As it turns out, Refsdal is actually 9 billion light years away, and since the supernovae is a one-time event, we can conclude that gravitational lensing has allowed us to photograph the supernovae 9 billion years in the past, almost three-quarters of the way to the beginning of the universe. Because of an odd phenomenon in spacetime, and lucky happenstance, we get to observe the death of a star billions of years ago. And not only that, but we get to see it multiple times.

While in most drawings and explanations of gravitational lensing, we see the light being bent around a perfectly spherical bubble of gravitational attraction, whereas in reality that gravitational bubble can be warped. Essentially, the path around the cluster can differentiate the light paths enough so that some take longer than others. The direct effect of this differentiation is that we get to see the supernova over and over again, as the light paths keep hitting us at different times. We only observed one so far, in November of this year, but we can assume that we missed the explosion being replayed twice in the 20th century, and we can even predict that another will appear in the next 1-4 years.

And there we have it! We have successfully predicted the future, although admittedly in a fairly specific way. But the usefulness of this situation spans more than just the coolness of predicting the future and seeing into the past. “It’s a wonderful discovery,” said Alex Filippenko, a professor of astronomy at Berkley and member of Kelly’s team. “We’ve been searching for a strongly lensed supernova for 50 years, and now we’ve found one. Besides being really cool, it should provide a lot of astrophysically important information.” For instance, with more research the scientists may be able to gain insight into how supernovae work, how gravitational lensing work, in turn the nature of spacetime, and even how dark matter works, which makes up a large portion of the gravitational pull affecting the light from the supernova’s original explosion. Discoveries like these are not only exciting and interesting, but they allow us to continually understand more and more about the world, and universe, around us.

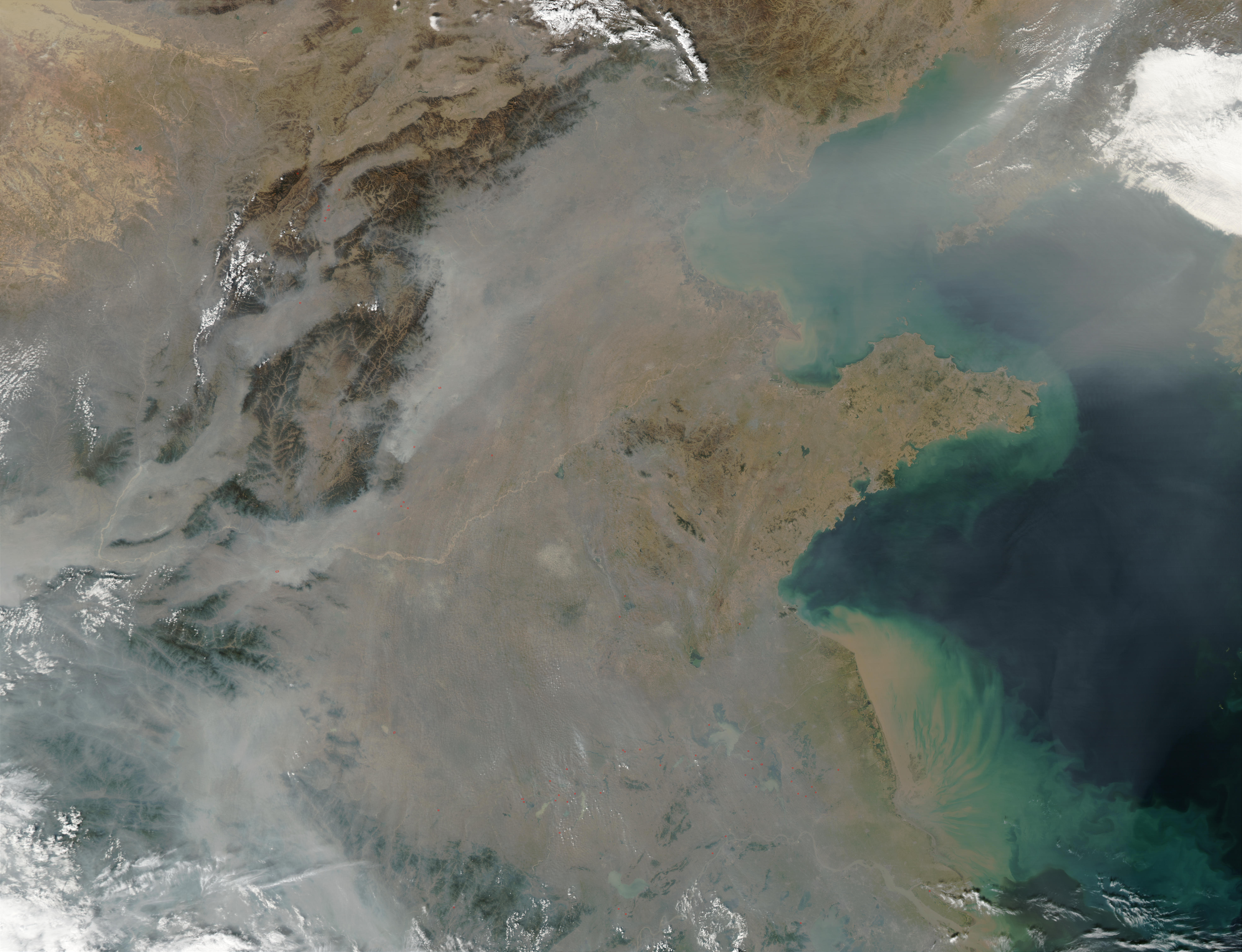

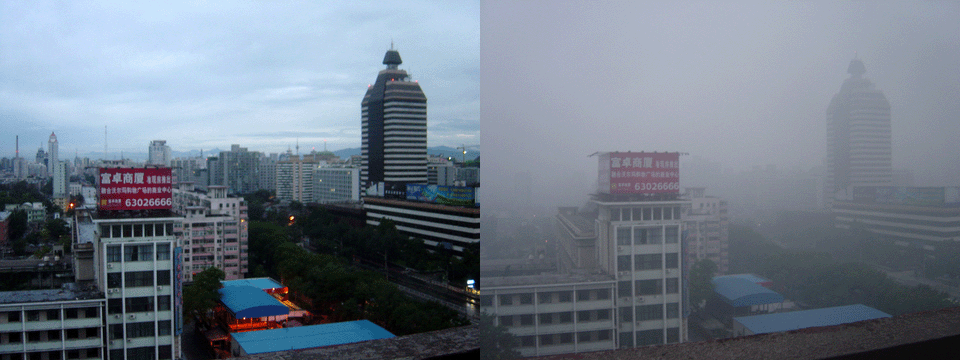

China’s Pollution Problem Explained

09 years

Just this week, China issued a “red alert” for the country’s capital, Beijing. The alert was used as a warning to their population that the smog levels in Beijing and the surrounding area has risen to a dangerous level, that is, even more dangerous than before. In response, schools are advised to be shut down, the number of vehicles on the roads will be restricted, and all factories and construction sites will be temporarily closed. And it’s not as if no one could see this coming, as China’s pollution problem has only worsened in recent years. Wearing masks over your mouth, like the type you are given at the doctor’s office when you are sick, has become commonplace all over the city, with some people even donning large filtering masks instead. In fact, companies are now taking advantage of this demand, releasing a range of masks in different colors and styles. Beijing has reached a point where the pollution is inhibiting daily life in a major way: outside of buildings, the ever-present smog enveloping the city means that simply walking outside has come dangerous.

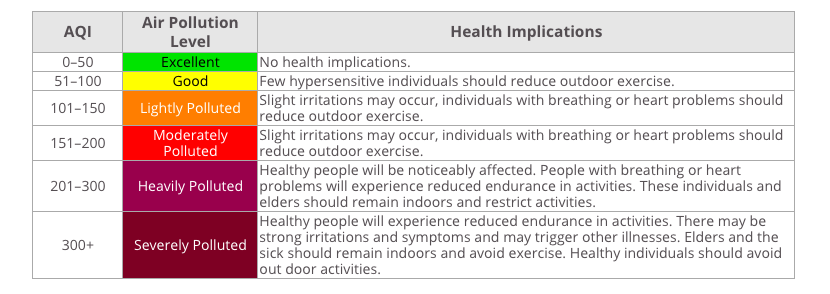

Although it’s clear from a glance at the smog that Beijing’s pollution situation is more than just unhealthy, it’s always good to check that with science. An AQI, or Air Quality Index, is the way that most countries around the world measure the level of pollution in a simple way that the public can understand and act upon. In China, the AQI is measured very frequently throughout major cities and often influences behavior, e.g., whether they go outside at a given time. The recommended, healthy AQI level globally is from 0-50. Here in the Bay Area, where I live, the AQI is around 15. In the city of San Francisco it rises to around 40, which is still good. In London the AQI is around 75, which is worse but still considered acceptable. The exact hierarchy of the severity of the pollution varies between countries, but both China and the United States use a system that is very similar to the table below:

At the time of writing, the AQI level in Beijing was 323. Less polluted areas of the city have an AQI of 220, worse areas an AQI of a whopping 445, just 55 points shy of literally being off the scale (typically AQI is 0-500). Clearly, China have dug themselves into a whole that seems very difficult to escape. “I’m used to the smog,” Wolf Hu, a resident of Beijing, told CNN. “I’d find a day when the sky is blue unusual.”

We can all agree, even the Chinese government, that the air in China’s major cities is extremely hazardous and puts their population in unnecessary danger and discomfort. But recent studies have shown that the incredibly high pollution levels in China do much more than put their population in discomfort. The most dangerous pollutant, PM2.5, where PM stands for particulate matter, targets particulates that are 2.5 microns in diameter or less. For comparison, a human hair is around 40-50 microns across. Particular matter consists of dust, soot, smoke, liquid droplets, or anything that happens to be floating around in the air at the time. While particulate matter is incredibly small, if any happens to float into your lungs when you breathe, the particles can cause a lot of damage, including increasing risk of a variety of heart and lung related diseases.

It should be no surprise then, as the PM2.5 level all over the country is very high, that the population have started to feel the consequences. Using new data released by the Chinese government, a study done by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley found that 1.6 million people die from heart, lung, and stroke problems stemming from breathing pollution in China every year. That’s 4,000 people dying every day, 17% of all of the annual deaths in the country. The very same study also found another eye-opening statistic: breathing in the pollution in Beijing and other cities in China does equivalent damage to your lungs as smoking 40 cigarettes per day does.

The state of China’s air is, to say the least, abysmal. The term “airpocalypse” has already been coined to refer to the problem. To be honest, it like the setting of a young-adult dystopian novel than the state of one of the global superpowers of the 21st century. To their credit, the Chinese government has (belatedly) recognized the problem. Li Keqiang, the Chinese Premier, has stated that China must “fight with all their might” against pollution, and has previously “declared war” on pollution, although no real plan or action has been taken to reduce pollution or cut emissions. China and the United States created a joint agreement for China to slow, peak, then cut carbon emissions by 2030, and both nations attended the landmark Paris climate summit in which leaders from around the world are collaborating on a solution to limit climate change. We may finally be going in the right direction, but it will certainly take an effort from the entire world to try and keep the world a clean, vibrant, and vivacious place, free of carbon. If there’s one thing we can all agree on, it’s that a world where a blue sky is rare and the outside is feared is no place that anyone wants to live in.

Sources:

http://www.cnbc.com/2015/08/18/china-air-pollution-far-worse-than-thought-study.html http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/dec/07/beijing-pollution-red-alert-smog-engulfs-capital http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/dec/16/beijing-airpocalypse-city-almost-uninhabitable-pollution-china http://aqicn.org/city/beijing/ http://www3.epa.gov/pm/ http://www.cnn.com/2015/12/07/asia/china-beijing-pollution-red-alert/ http://www.wikiwand.com/en/Air_quality_index#/United_States http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/mar/05/china-vows-to-fight-pollution-with-all-our-mightThe Almost Impossible Ethical Dilemma Behind Autonomous Cars

09 years

You’re driving down the road in your Toyota Camry one morning on your way to work. You’ve been driving for 15 years now and pride yourself on the fact that you’ve never had a single accident. And you have to drive a lot, too; every morning you commute an hour up to San Francisco to your office. You pull into a two-lane street lined on both sides with suburban housing, and suddenly realize you took a wrong turn. You quickly look down at your smartphone, which is running Google Maps, to find a new route to the highway. When you look back up, you’re surprised to see a group of 5 people, 3 adults and 2 kids, have unknowingly walked into your path. By the time you or the group notice each other it’s too late to hit the break or for the pedestrians to run out of the way. Your only option to save the 5 people from being injured, or even killed, by your car is to swerve out of the way… right into the path of a woman walking her child in a stroller. You notice all of this in the half a second it takes you to close the distance between you and the group to only 3-4 yards.

You now have but milliseconds to decide what path to take. What do you do? But more to the point of this article, what would an autonomous car do?

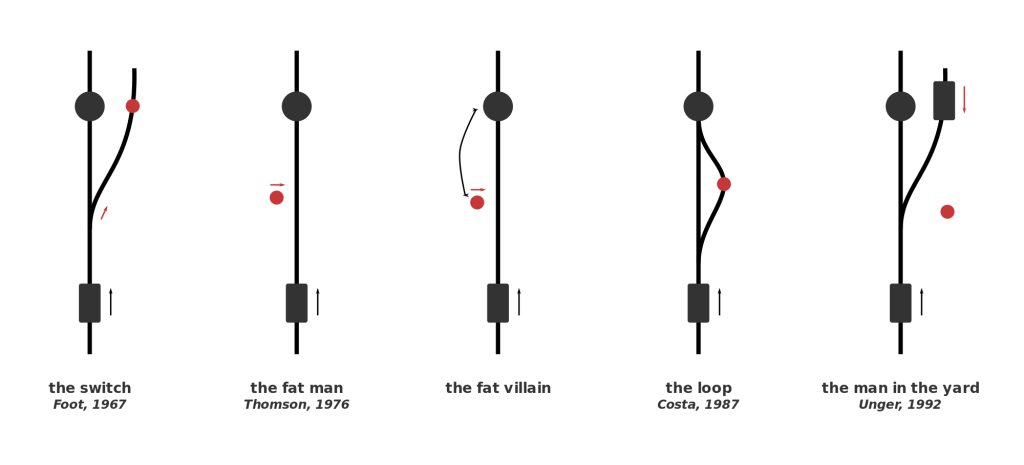

That narrative is a variant of the classic situation known as the Trolley Problem. The Trolley Problem has many variations, some more famous than others, but all of them follow the same general storyline: you must choose between accidentally killing 5 people (e.g., hitting them with your car) or purposefully making an action (e.g., swerving out of the way) that kills one person. This type of situation is obviously one that no one wants to find themselves in, and is so unlikely that most people avoid it their entire life. But in the slim cases where this situation occurs, the split-second decision a human makes will vary from person to person and from situation to situation.

But no matter the outcome of the tragic event, if it does end up happening, the end result will be generally be the fault of a distracted driver. What will happen, though, when this decision is completely in the hands of an algorithm, as it will be when autonomous cars ubiquitously roam the streets years from now. Every new day autonomous cars become more and more something of the present rather than the future, and that leaves many worried. Driving has been ingrained in us for century, and for many, giving that control up to a computer will be frightening. This is despite the fact that in the years that autonomous cars have been on the roads, their safety record has been excellent, with only 14 accidents and no serious injuries. While 14 may seem like a lot, keep in mind that each and every incident was actually the result of human error by another car, many of which were the result of distracted driving.

I’d say that people are more worried about situations like the Trolley Problem, rather than the safety of the car itself, when driving in an autonomous car. Autonomous cars are just motorized vehicles driven by algorithms, or intricate math equations that can be written to make decisions. When an algorithm written to make a car change lanes and parallel park has to make almost ethically impossible decisions, choosing between just letting 5 people die or purposely killing 1 person, we can’t really predict what it would do. That’s why autonomous car makers can’t just let this problem go, and have to delve into the realm of philosophy and make an ethics setting in their algorithms.

This won’t be an easy task, and will require everyone, from the car makers to the customers, thinking about what split-second decision they would make, so they can then program the cars to do the same. This ethics setting would have to work in all situations; for instance, what would it do if instead of 5 people versus one person, it was a small child versus hitting an oncoming car? One suggested solution would be to have adjustable ethics setting, where the customer gets to choose whether they would put their own life over a child’s, or to kill one person over letting 5 people die, etc. This would redirect the blame back to the consumer, giving him or her control over such ethical choices. Still, that kind of a decision, which very well could determine fate of you and some random strangers, is one that nobody wants to make. I certainly couldn’t get out of bed and drive to work knowing that a decision I made could kill someone, and I’d bet I’m not alone on that one. In fact, people may even avoid purchasing an autonomous car with an adjustable ethics setting just because they don’t want to make that decision or live with the consequences.

So what do we do? Nobody seems to want to make kind of decisions, even though it is absolutely necessary. Jean-Francois Bonnefon, at the Toulouse School of Economics in France, and his colleagues conducted a study that may help us all with coming up with an acceptable ethics setting. Bonnefon’s logic was that people will be most happy with driving a car that has an ethics setting close to what they believed is a good setting, so he tried to gauge public opinion. By asking several hundred workers at Amazon’s Mechanical Turks artificial intelligence lab a series of questions regarding the Trolley Problem and autonomous cars, he came up with a general public opinion of the dilemma: minimize losses. In all circumstances, choose the option in which the least amount of people are injured or killed; a sort of utilitarian autonomous car, as Bunnefon describes it. But, with continued questioning, Bunnefon came to this conclusion:

“[Participants] were not as confident that autonomous vehicles would be programmed that way in reality—and for a good reason: they actually wished others to cruise in utilitarian autonomous vehicles, more than they wanted to buy utilitarian autonomous vehicles themselves.”

Essentially, people would like other people to drive these utilitarian cars, but less enthusiastic about driving one themselves. Logically, this is a sensible conclusion. We all know that we should make the right decision and sacrifice your life over that of someone younger, like a child, or a group of 3 or 4 people, but when it comes down to it only the bravest among us are willing to do so. While these scenarios are far and few between, the decisions made by the algorithm in that sliver or a second could be the difference between the death of an unlucky passenger or an even more unlucky passerby. This “ethics setting” dilemma is a problem that can’t just be delegated to the engineers at Tesla or Google or BMW; it has to be one that we all think about, and make a collective decision for that will hopefully make the future of transportation a little more morally bearable.

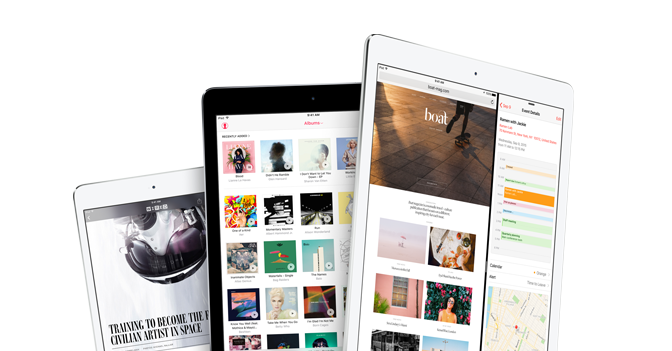

iPad Pro – What It Is And Who It’s For

09 years

Earlier this month at Apple’s annual product event, a new device was released that caught some by surprise. Historically, Apple isn’t a company that’s known for experimenting with different product lines, sizes, colors, or software designs. In recent years, Apple has started to branch out from their traditional iPhone and iPad lines, and brought the iPhone 5C, the line of iPhone Pluses, the iPad Minis, Apple TVs, and more. Clearly, they are trying to produce more options for their customers to choose from when buying one of their phones or tablets, which if anything benefits the customer more than Apple itself. But at the September 9th conference, Apple announced a product that baffled techies and average consumers alike: the iPad Pro.

Like the positioning of the Macbook Pro and the Mac Pro, the iPad Pro is essentially just a higher performance iPad. The specs for the device are promising; most importantly, the resolution is better than the high-end Macbooks, at 264 pixels per inch, even beating out it’s newfound competitor, the Surface Pro. It has a 10-hour battery life, which is fairly good for the device’s size, and again beats out the Surface at 9 hours. But of course, the one spec that surprised everyone was the size: the iPad Pro has an insane 12.9-inch screen.

That’s 3.2 inches bigger than the recently released iPad Air 2, the latest installment in the iPad line. Now, while the product had been rumored for months, far fewer could have expected a super-sized iPad over a year ago, in part because, unlike the upsized iPhones few really saw the need for a giant iPad. The iPad Air 2 is already a pretty good size at 9.7 inches, and adding three inches on to that doesn’t really rectify the $300 price increase. Sure, as Apple has been partly marketing the device, the iPad Pro would be a great device for watching and consuming media, like watching movies, readings articles, and perhaps even playing games. The iPad Pro could easily replace your laptop as your main entertainment consumption device, although personally, I would just spend the extra $200 to get the Macbook Air of the same size, as certain functionalities of the Macs over iPads are important to me and my work. And to be honest, the iPad line is starting to feel a little like this:

That’s not to say that the iPad Pro is a bad addition to the iPad line. If anything, the addition to the product line helps make the iPad line a better fit for consumers or professionals with specific use cases. For instance, one example that everyone came up with simultaneously after the iPad Pro’s release was for artists. The iPad Pro is a great size for a digital art pad, and the excellent display only makes adds to the use case. This hypothesis, that Apple was targeting artists, was only reinforced by their release of new product, an almost parody-esque product, the Apple Pencil.

Apple Pencil is, as you probably guessed, a stylus. Designed to work with the iPad Pro, Apple Pencil is Apple’s attempt at getting into the stylus market, although the Pencil may only work with the iPad Pro. The stylus is actually a very good stylus; it has a very good response time when in use, is pressure sensitive, and overall has a very fluid and smooth feel to it. That’s all and well, and will definitely help out artists when using the iPad Pro, but the reason that this device is so surprising is because of Steve Jobs’ views on the product category. Although Jobs isn’t around to keep Apple going anymore, he did have some opinions that surely shaped the way Apple progressed each year, and this is the first time we’ve seen evidence of Apple disregarding what he thought. Jobs has a strong opinion against styluses, expressing how he thought they were cumbersome and hard to keep track of. “Who want’s a stylus?” he said in 2010 keynote speech. “If you see a stylus, they blew it.”

The Apple Pencil aside, the iPad Pro is an interesting product. No doubt it’s a high-quality device; it has great specs and the big screen just makes it a great content viewing platform. But for 800$? I certainly wouldn’t spend the money, but for people who can (or just want to) it’s a great purchase, as long as they know why they want it. If you’re just looking for an iPad, the iPad Air 2 is a great choice. But the iPad Pro is the kind of niche device that’s great for the people who have a reason to use it, such as artists, but maybe not as profitable for the company, and certainly not the type of device you expect Apple to release. Still, that may show they are trying to branch out into more product types and categories, which very well may lead to some great products in the future.

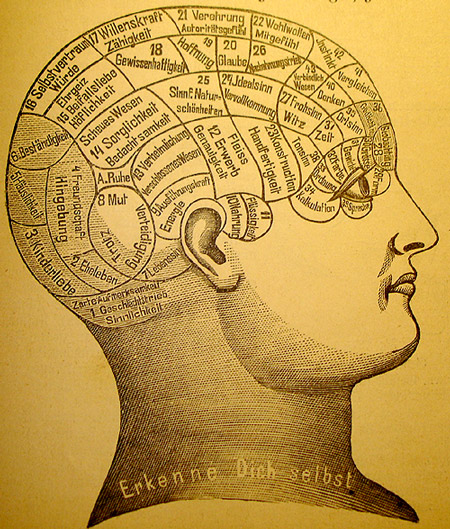

Science Journals May Not Be As Reliable As We Thought

09 years

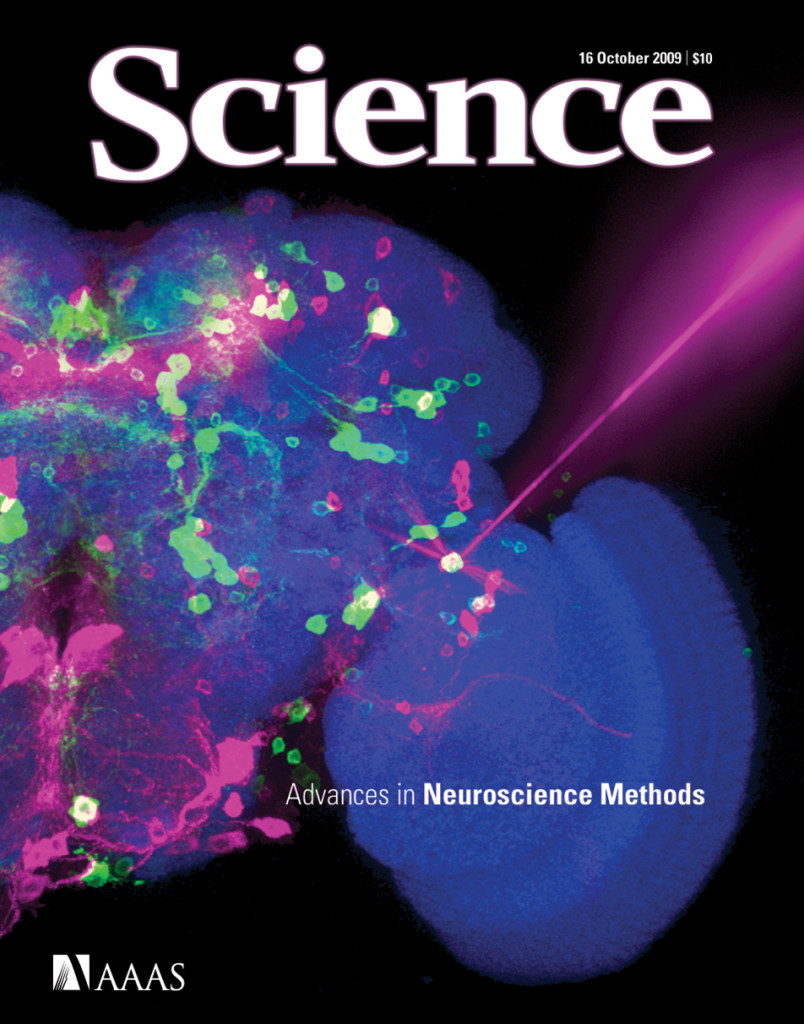

Science journals are a great way to learn about discoveries in a wide variety of fields, and reading them keeps you scientifically literate and up-to-date on new advances. Journals such as Nature and Science have become increasingly popular outside their core “hard science” constituencies, partly due to successful outreach efforts including new podcasts, videos, and free web content. These growth initiatives have not diluted the top-tier scientific stature of the publications –they remain at the pinnacle of the scientific community. Because of the journals’ exclusivity and reputation, most readers naturally assume the findings featured in their articles are true. But the reliability of published scientific research has come under scrutiny recently, ironically in a paper published in Science itself that called into question papers published in leading psychology journals.

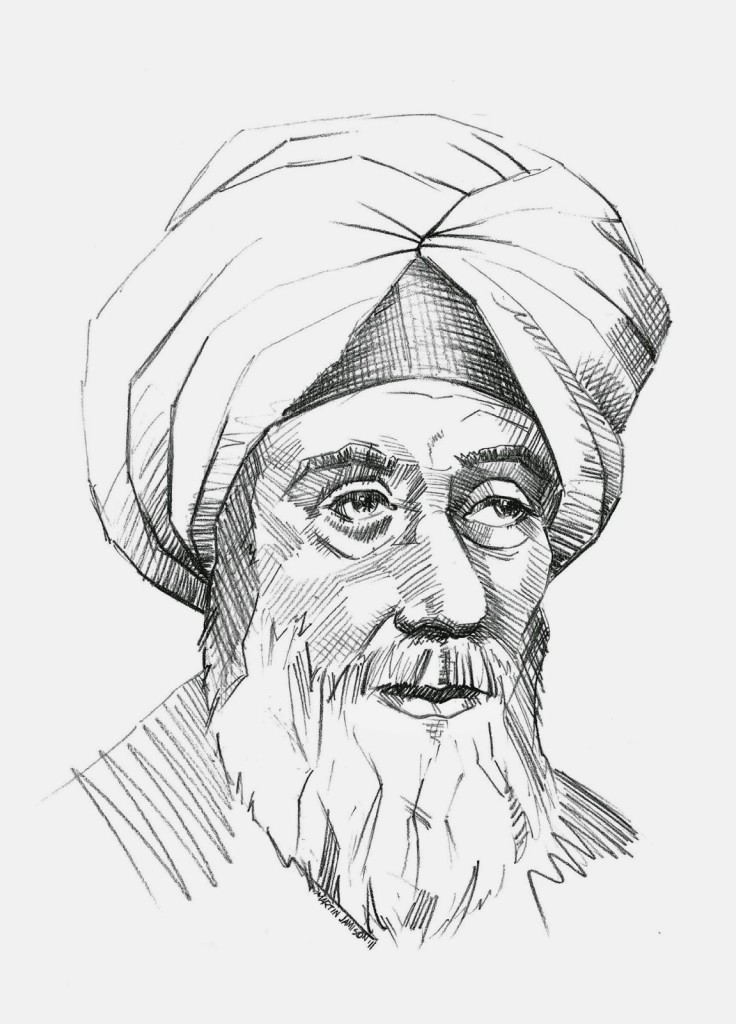

The study was simple. They would take 100 papers published in top psychology journals and try to replicate their results. Replication is a keystone of science: if I get one result and you get another doing the same study or experiment, then we can’t say for sure that either my or your result is true. The scientific method has included replication for 500+ years, all the way back to the Muslim scientists of Baghdad. So, when modern scientists replicate old psychology studies, you can expect them to get the same result, right?

Well, that’s the problem. Many of these studies are so hard to replicate that the effort is never even attempted. Part of the problem is that scientists won’t get a headline study published with a title like “Blah Blah Study From A Year Ago Done Again And The Same Thing Happened!” New, exciting studies are what get published, and that’s what a scientist wants: to get published. But let’s assume that not all researchers are like this, and some do science purely with a goal of advancing and confirming science. It’s really hard to be this person, mainly because replicating science is just not easy. It’s easier to just do your own studies and get your own results.

Ibn al-Haytham, the Muslim scientist who helped other scientists reproduce his work better than modern scientists do today.

So when this study was completed, replicating 100 psychology studies, their results were disappointing. By one of the replication success indicators from the publication, only 36% of the studies returned the same results as they did the first time. What that means is that more than half of the studies replicated after they were published in a top psychology journal failed a large part of the scientific method. This puts the whole psychology field into question. Should more researchers be replicating past studies? Certainly, as Brian Nosek, a psychologist working on the Science study said,

“It would be great to have stronger norms about being more detailed with the methods… If I can rapidly get up to speed, I have a much better chance of approximating the results.”

Basically, scientists and researchers should include a detailed description of how they did the study, so any other scientist could easily repeat and prove or disprove your results. Even Ibn al-Haytham, a Muslim scientist born in 956, did this by including incredibly detailed instructions on how to carry out his experiments in his book Book Of Optics, and scientists today should put more care into helping with replication. It even has a name: the crisis of irreproducibility. And what’s even more scary is that psychology has to do with our mind and how we behave, so these studies that have, currently, less than a 50% chance of the results being true affect how people live their lives dramatically. But in the future, scientists (and journals) have to take more care in the reproducibility of their studies, because without reproducing studies, we can never really know what’s true and what’s not.

Why Other Companies Should Follow Alphabet’s Lead

09 years

For as long as it has existed, the public has identified the Google brand with the ridiculously popular search engine under the same name. Since 1998, Google search has grown exponentially while staying pretty much the same, yet the company Google has expanded aggressively into fields well beyond search, both through acquisitions such as YouTube and Nest, and organically via the company’s extensive R&D initiatives such as Google Glass and the company’s autonomous car. Still, this has all fallen under the good old multi-billion dollar umbrella of Google. That all changed last week. Not that initiatives inside Google have fundamentally changed; the profit driver continues to be search and advertising, with many long-term prospects hoping to flower eventually. Nevertheless, the restructuring of management lines arguably has dramatic long-term implications, in my opinion for the better.

In a nutshell, Google essentially created a holding company called Alphabet that owns Google and many smaller companies that Google has acquired/created, such as Nest and Calico (Google’s longevity initiative). Alphabet is now a portfolio of enterprises managed by founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, many with distinct CEOs who have a fair amount of independence. This shift came as a shock to everyone outside of Google (and likely many inside the company), sounding more like one of the company’s classic April Fool’s jokes than a typical corporate maneuver. Renaming a company with one of the top business brands in the world? Insane in many respects, not to mention handing the CEO of “Google Classic” to another executive, Sundar Pichai.

So why is this a good idea, and why should other companies consider following Google’s lead? It really comes down to what they are trying to accomplish as a company. In the announcement letter that you can read at abc.xyz, they wrote the following, which helps explain their reasoning behind the change:

“As Sergey and I wrote in the original founders letter 11 years ago, ‘Google is not a conventional company. We do not intend to become one.’

Alphabet’s initiatives are far-flung and have the potential much more than Google’s traditional “cash cow” businesses to change the world. It’s hard not to see some of Alphabet’s initiatives becoming wildly successful and ultimately spinning out into independent, and large, public companies. For instance, I previously mentioned Calico as one of the companies Alphabet is keeping under it’s wing. Calico is a scientific research and technology company; their ambitious goal is to research and eventually create ways to elongate life and let people live healthier. That is a goal, although ambitious, if reached with the help of Alphabet could very well change the world in a major way.

What really excites me about Alphabet is that they’re doing precisely what I would do with all that money and resources: create and finance projects that will change the future. Google the search engine has become a very conventional business in the Internet age, but Google the company aspires to much more that just rolling in the cash and adding its existing product lines (I hate to say it, but I’m looking at you, Apple). In an age of tech titans, companies such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft are all angling to stake their claim to the future. And under Alphabet, Google aims to establish a leading innovation platform by “letting many flowers bloom.” Rather than sticking to a couple odd ventures and mainly staying a conventional company, Alphabet lets Google expand into a business set on creating a better future. And if this change in corporate structure will help facilitate that, then I say go for it.

If you want to read the original Alphabet announcement letter, click HERE.